11 Writing a literature review

The first chapter of many PhDs is often a place for a literature review. Writing a review of the literature is actually a very useful task to undertake during your PhD. Firstly, it will get you familiar with all of the relevant literature in your field. It will give you some idea of the historical context of your subject area. And it’s especially good to help you spot gaps in the literature that may not have been realised before, perhaps giving you ideas about pitching grant proposals. As an Early Career Researcher, if you haven’t undertaken a review in your subject area, then you should seriously consider it.

11.1 Having a purpose

Writing a literature review is easiest when you have a clear purpose. The objective can be tight, or can aim to use the literature in order to answer a broader question. Either way, having a clear purpose for your literature review will help you to define exactly what literature you’re looking for.

Without an aim, a literature review can be extremely daunting. There will be literally no end to the literature that you could include and it may well overwhelm you. If your question is more broad, it will help to define a clear time period in which you are searching for literature. For example, you may want to just consider the last 10 years. Remember that the amount of literature is increasing almost exponentially and so if you are covering the same ground as a previous review a lot can happen in 10 years.

If your aim is quite narrow then you can legitimately cover all of the literature. This may require delving back more than 100 years. But as we know the first journal only began around ~150 years ago.

If you want your review to have an objective or statistical angle on the literature then consider writing a systematic review or a meta-analysis.

11.2 Systematic reviews

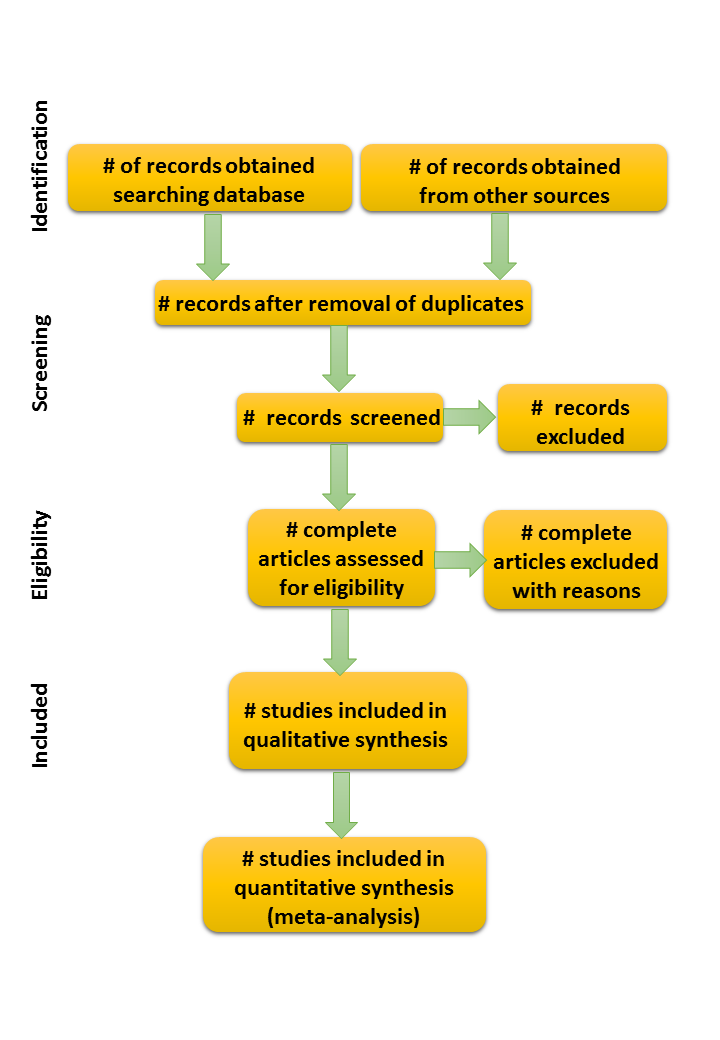

A systematic review is when you define your search criteria and the databases that you want to use and then consider all of the literature that comes out. You will need to provide clear criteria for the inclusion of literature. As well as explaining exactly how you decide to include or exclude papers that result from your search terms. Systematic reviews require a flow diagram to show how this literature was included or excluded (Moher et al., 2009 see Figure 11.1). Many journals (especially those linked to PubMed) now insist that a Prisma flow-diagram has to be ‘Figure 1’ of any systematic review submitted. Simply replace the text in Figure 11.1 with relevant numbers as appropriate in your systematic literature review. You can also add boxes as necessary. Note that the need to produce the Prisma flow-diagram means that you should keep good records of the results (and date) each time you conduct a literature search. You should also retain the actual search term used together with a file of the results.

FIGURE 11.1: The Prisma flow diagram after Moher et al (2009). Text inside the boxes is replaced by the author with the corresponding numbers of records, articles and studies as they were filtered during their systematic literature review, and (if appropriate) the final meta-analysis.

In my opinion, a systematic review is less subjective than a review where the author is essentially cherry picking the literature in order to tell the story as they see it. It also allows you to conduct statistical tests in order to answer some of your questions: i.e. a meta-analysis. Lastly, it avoids one of the oldest problems in science: confirmation bias. Non-systematic reviews tend to simply look for articles that back up the author’s own view. Too many old reviews are really just written by academics seeking to confirm their standpoints, and so moving forwards we must place the emphasis on being objective through systematic reviews. This view is now growing so that increasing numbers of journals will only accept a review if it is systematic.

11.3 Meta-analysis

A meta-analysis is a particular type of review that will allow you to use the results from a range of literature to answer hypotheses from a lot of different studies. This should be combined with a systematic review to ensure that your selection of literature does not contain any bias. It is important that you understand how to analyse a meta-analysis before you start to collect data from the literature. There are a number of good guides that have been published (e.g. Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution, 2013), and becoming familiar with the most recent techniques published in your target journals is always a good idea. As for any review, you should try to make sure that you have sufficient capacity to take on your particular question.

Increasing numbers of datasets are now becoming available online, and you also have the potential to write to authors and ask for actual data instead of trying to scrape it from images in publications. Once you have conducted a meta-analysis, you will understand why placing your raw data online is so important, and this should never be behind a paywall.

11.3.1 Meta-analysis for publication bias

Workers have used funnel plots from meta-analyses to determine whether or not a question has received some kind of publication bias (Sterne & Harbord, 2004). Example funnel plots and an explanation of publication bias can be found in Part IV.

11.4 Using Google Scholar

Google scholar has distinct advantages over other literature databases as it searches words inside the contents of an article, not just in the title, abstract and keywords (like Scopus and WoS). However, the output style of Google Scholar is infuriating as it resists being able to capture search results into a simple table (database) format. In addition, it does not support Boolean search operators, and includes a far broader range of literature, and linking citations (Martín-Martín et al., 2021).

Help is at hand for those of you who would like to use Google Scholar and get a database output with the publication of Publish or Perish software (Harzing, 2007). The original purpose of this software was to calculate personal research metrics for promotion purposes, and it still does all this. But it also provides a single platform for searching many different literature databases: Scopus, Web of Science, Microsoft Academic (now discontinued), Google Scholar.

Google Scholar has an important attribute over many other databases in that it returns results in languages other than English. Using only English to provide the basis for your review might lead you to draw an unreasonable conclusion with a literature bias (Nunez & Amano, 2021). Language is only one of several potential biases in a literature review (Amano & Sutherland, 2013).

11.5 The meta-analysis

A meta-analysis is a type of systematic review that uses the results of all of the studies included in order to provide a synthesis. While more powerful than a systematic review alone they take an awful lot of work. If you are expecting to get a lot of literature then consider putting a team together in order to conduct a meta-analysis.

However, conducting a meta-analysis on a small number or articles (<20) could lead to spurious results. In other words, they might not be a good solution for a very small subject area. Unless your questions have had sufficient numbers of investigations, you would be better to assess it qualitatively.

11.5.1 Combining topics by combining people

Reviews become especially insightful when you combine topics together. To do this you may want to find somebody else who is an expert on the literature in that field. This might be somebody in your lab group, or it might be someone in your wider network. Bringing together a set of like-minded people for a review is a very powerful way in which to create an important and potentially powerful network of collaborators.

This brings me to another very important point. Share your enthusiasm for your topic. Remember to talk to people around you, both in your laboratory and in your department about the work that you’re doing, and tell them about the interesting things that you’re finding. If they also tell you about their work, then you may find that you have somebody to combine your literature review with in a novel angle that’s never been thought of before. The paper that results could be a smash hit.

11.6 Don’t try to do too much

Whatever your aims were before you started compiling the literature, remember to remain flexible as you proceed. It’s hard to know exactly how many papers you will encounter on a particular subject until you’ve conducted the search. If you’re prepared to remain flexible while conducting your review it may save you from overreaching. Always be open to reducing the scope of your review or spotting new questions or issues while you’re reading that may be better than your initial idea.

11.7 In summary

If you have got to this stage of your career and have not yet done a literature review then now is the time. You should already know a large chunk of the literature in your particular area and you will be looking for future questions to tackle in your early career. Conducting a literature review at this stage will not only help you to highlight unanswered questions and interesting topics, but it will get your name out there. Once you’ve done it you’ll be glad you did.