18 Submitting a paper to a journal for peer review

This chapter deals with the process of submitting a manuscript to a journal (Figure 18.1), and what to expect once this is done. It takes time to submit a paper using most existing editorial management software. Detailed information is given on many of the parts, mentioned here, in later sections of the book. Be aware that although it does take a lot of effort to get a manuscript ready for submission, once it is submitted, there is a lot more work taken on by a larger group of people who are (usually) not paid, and who are undertaking the work associated with your manuscript in addition to their ‘day jobs’.

Most of the information required for submission is easy enough to provide, but they insist on having it entered in such an unfriendly way that it makes it all very painful. Believe it or not, they have improved over time. As this work is so tedious, it’s worth reflecting why they need all of this information upfront before anyone even decides whether or not they want your paper. The reality is that all of this metadata (data associated with your manuscript) is really only of use if the manuscript is accepted. Otherwise, you are really just stuffing the database of the publisher full of information that they may (and likely will) use to spam you in the future. The only data that they must have on submission is your name and contact details, and the verification that you’ve adhered to the journal’s ethical requirements (which you could do in a letter to the editor). Some of the rest will be of use to the editor when deciding who to allocate your submission to, but the vast majority of the metadata are only used if your article is accepted - and then they become vital.

Once accepted, metadata about your manuscript lies at the heart of the ability for CrossRef to link you, your co-authors and their ORCID accounts together with your manuscript using a DOI. All of this information is held in a header file of the published webpage so that Google Scholar can scrape it into their database. It’s also used by all of your automated referencing software plugins. Having this data entered accurately means that the following processes will flow nicely. Doing a sloppy job will mean that those who rely on such services might well mis-cite your paper, get your name wrong, or one of lots of other potential issues. Most of the major publishers now use this metadata to make up the author information (and addresses) on the front page of the typeset paper. Be aware that when they appear wrong on your proofs, it’s likely because you (or the corresponding author) didn’t enter the metadata correctly.

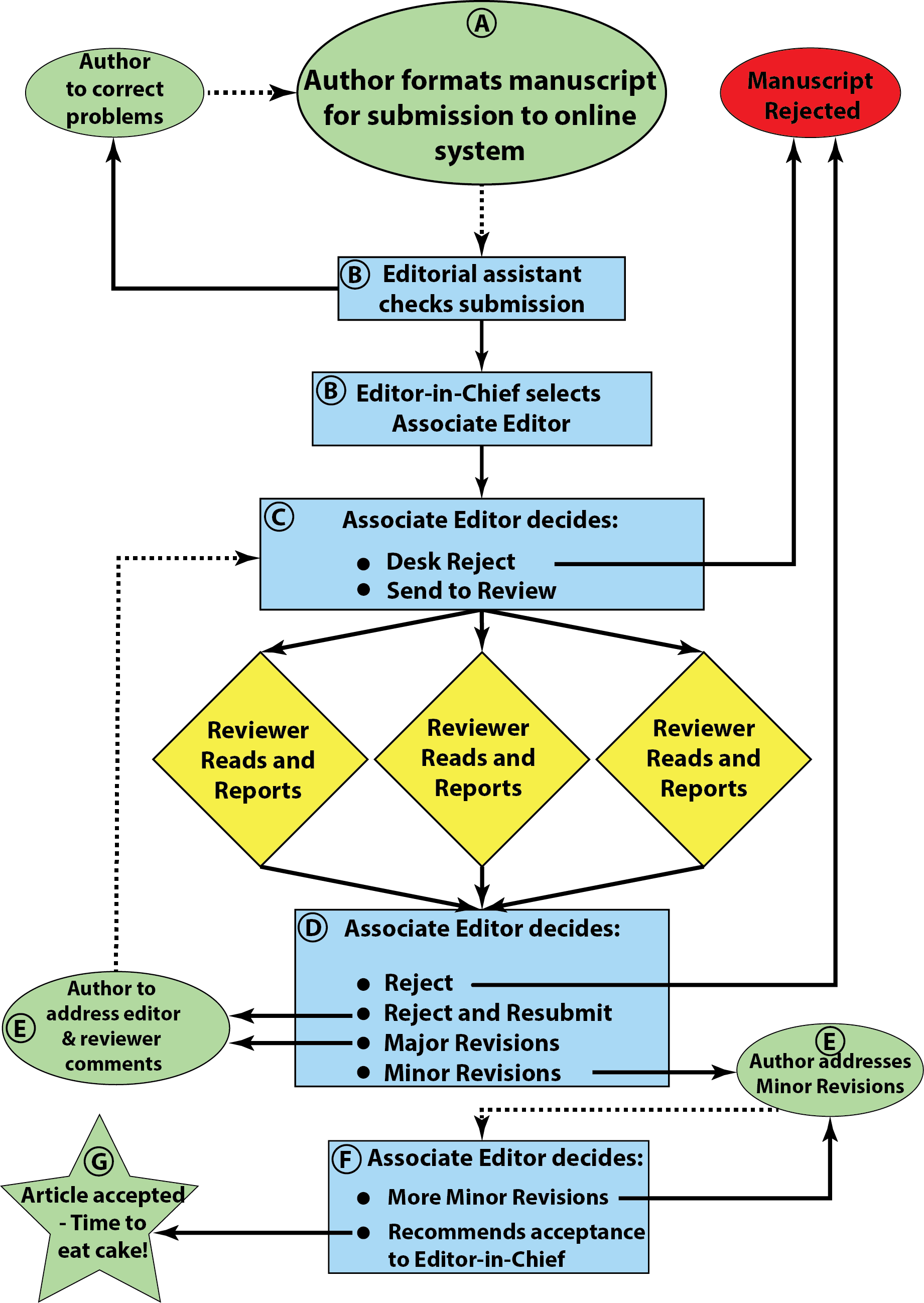

FIGURE 18.1: This schematic demonstrates the editorial work-flow of a ‘typical’ journal. Ovals show actions by authors which have dotted lines, while rectangles show work done by the editorial team of the journal with solid lines. Referees are shown as diamonds. Letters in circles refer to the sections of the text (below). All arrows are potential places for delays.

18.1 A typical submission work-flow

The steps A to G (below) all refer back to letters in circles in Figure 18.1. Remember that most of the actions described below are also the subject of later sections in Parts II and III of this book.

A - formatting and submitting

- Targeting journals for submission: there are a lot of journals out there, and you need to make sure that you are submitting your paper to a journal in the right subject area (there is a detailed chapter on this subject). Remember to keep your ordered list of journals that you prepare so that you can refer back to this in the case of rejection.

- Prepare your manuscript according to the journal guidelines: this may require a lot of work especially if the journal requires full formatting on first submission. Some journals require additional items such as graphical abstracts, so make sure that you know what is needed before you start to submit. A checklist to run through before submission is available here, to which you should add any journal checklist from their instructions to authors. Circulate this final version among your co-authors. This is a good time to gather the needed meta-data for submission.

- Get all the files and metadata ready for submission. In addition to the manuscript, figures and tables, you’ll (usually) need a cover letter, key-words, recommended (or opposed) reviewers, and addresses (with ORCID numbers) for all authors. All these items should already have met with the approval of your co-authors.

- For the purposes of this section, I am assuming that you are the corresponding author. This is something that you should learn to do. Being the corresponding author carries some extra duties as they are responsible for making sure that all the other authors are in agreement about the contents of the paper before submission. They are responsible for gathering all of the necessary information about each of the authors on the title page.

- Uploading your manuscript to the editorial management software requires time and preparation. Give yourself a good couple of hours for this process, and be aware that it can be frustrating. Friday afternoon might not be the best time. You may well need to refer back to your co-authors if you don’t have their relevant information. As corresponding author, it is courteous at this point to send a copy of the submitted version (usually the journal provides a pdf of the submission) to all of the other authors for their records.

B - Editorial assistant and/or editor check the manuscript

- Once submitted to the system, your manuscript is usually checked. In bigger journals, this will often be done by an editorial assistant, while in smaller journals, the editor-in-chief may be responsible for moving all manuscripts. before being passed to the editor. You may get it sent back if the meta-data is wrong.

- Once the editor (often Editor-in-Chief) has your manuscript, they will decide which Associate Editor (AE) will handle it.

C - Associate Editor takes over

- The AE should read the manuscript and may desk reject it if they feel that it won’t make it through review. An AE rejection isn’t great news as AEs don’t always have the best experience in knowing what will and what won’t make it through the review process. The editor usually has more experience. Hopefully, this won’t have taken long (1 to 2 weeks) and so won’t be very painful. This rejection may be fair or unfair, but it’s done and there’s nothing much you can do except return to A (above), but see later sections.

- Normally, your manuscript will be sent out to review and you can expect to wait 4 to 6 weeks (good), but sometimes up to 3 months, for a decision. If it’s away for over 3 months, you should definitely make a query on the editorial management system. Unsurprisingly, authors feel more unhappy with the review results the longer the process takes (Jiang, 2021).

D - Reading the reviews

- Once back from review, you’ll get an email from the editorial management system with the decision.

- Reject and resubmit: This is a category that means you need major revision, but the journal doesn’t want the time that it takes to do this on their journal processing statistics. In many journals, this result has replaced ‘major revision’. Back to step 3 with a track changes manuscript and response letter to reviewer comments.

- Major revision: essentially the same as reject and resubmit. Both reject and resubmit and Major revision result in your manuscript being reviewed again. You’ll need to carefully prepare both the manuscript and the response to reviewers as the reviewers will see both. Back to step C with a response letter.

- Minor revision: is unusual after the first round of review, so if you get this decision first time it’s something to celebrate. You may have already done one (or more) rounds of Major revision before you get here. After addressing the Minor revisions, your manuscript should now only be assessed by the AE, so you should address your responses to them.

- Accept without further revision: is practically unheard of on first submission. Your manuscript may have already undergone some peer review (maybe as a preprint or in another journal), or in previous rounds of review. This decision is likely a recommendation from the AE to the Editor-in-Chief.

E - Revising and resubmitting your manuscript

- If you are resubmitting, aim to prioritise this to get it done in 2 to 3 weeks if possible.

- The reason is that the same reviewers are likely to be willing to look at your manuscript again within a month, and will remember all the points that they made. Similarly, the AE will remember all of the issues that they had. It’s hard to stress how valuable this is, as keeping it all fresh will result in a swift response.

- If you don’t or can’t manage to get your responses back quickly, you might expect a rocky ride through the review process when you go back for the second round. The reviewers you had before might not be available, but the AE will be obliged to have at least 2 reviews again. This means that you may get new reviews. New reviewers are likely to throw up new issues, and could result in your manuscript getting rejected at this stage, or that you’ll have another Major revision decision, sending you back to step C with a track changes manuscript and response letter to reviewer comments. This drags the whole process on for much longer and reviewers and AEs are likely to look less favourably at your manuscript.

- A better result is when there are only Minor revisions. In this case the manuscript is simply bouncing between you and the AE and even if this happens more than once, it’s fine as long as you can keep the response time reasonable (within a couple of weeks).

- In either case, your rebuttal letter will be a very important part of your resubmission, and this will be covered in a later section.

F - Associate Editor recommends to Editor-in-Chief

- When the AE is happy with all of your Minor Revisions, they will make a recommendation to the Editor-in-Chief. The Editor-in-Chief may have some extra revisions that they would like to see, but these will likely be minor.

- It is unlikely that the Editor-in-Chief would disagree with the acceptance of any paper that an AE has signed off on.

- It is worth bearing in mind that the Editor-in-Chief does have the final say on whether or not your manusctipt can be accepted to the journal.

G - acceptance

- Hopefully your manuscript will now be accepted, and you are entering the last stages of the process. Your accepted manuscript should be sent to the publishers for copy-editing and typesetting, and you can get the proofs back very quickly (for some publishers). Most demand that the proofs are returned very quickly (often within 48 hours), and you should try to prioritise this if you can. If you can, please also send the proofs to the co-authors. The more eyes the better at this stage for spotting errors. Don’t expect to be able to change a lot in the proof process, it’s really just for catching errors. Carefully check all figures, tables and legends. It’s not unknown that typesetters cause problems when they make proofs (tables can be disasters). A detailed section is provided in Part III on what to do once your manuscript is accepted.

- If you (or a co-author) spot a fundamental error with your data or analyses at this point (or any of the other steps above), you should discuss it with all co-authors and decide what to do. It’s better to withdraw the manuscript now than to have to retract it later (see part IV).

Rejected

- If your manuscript is Rejected, take the comments of the reviewers on board. Think about it for a couple of days, and then set about revising the manuscript. However unfair you think the reviewers have been, there should be some important messages for you to consider carefully and discuss among the co-authors before going back to step A with the next journal on your list. More information to reflect on regarding a rejection is provided in a later section.

18.1.1 Remember that peer review is conducted by humans

The peer review process is not ideal, but it is worth remembering that it’s there to help improve your manuscript. The most prominent problems involve the time that the editorial team take to find reviewers and have them agree to complete reviews in a timely manner. In Figure 18.1, only 4 of the arrows are in the control of the authors, while at least 16 are within the editorial management process. Each one could be the source of your manuscript getting stuck. Throughout the process, you should be able to track the progress of your manuscript using the editorial management software online. More information on delays in the handling of manuscripts is provided in a later section.